The privatization of government is neither a niche nor novel phenomenon. In the contemporary era, examples abound in the form of government-sponsored enterprises in financial services like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, in managed care organizations for Medicaid and Medicare, and in the entire industry of defense contracting. In almost every government function, one can either find or imagine a role for private actors, often to a wide variance of outcomes - both positive and negative - for the recipients of these services.

The convergence of crises facing governments at all levels in 2020 has once again highlighted the private sector’s role in augmenting or supporting the performance of government functions. Consider, for instance, the role of fintech companies in government responses to economic relief in 2020. Numerous fintech companies played a role in facilitating the distribution of the largest stimulus package in American history, acting as a distribution layer between the government and both individuals and businesses. These products perform functions such as supporting unemployment claim filings, facilitating direct cash transfers, and advancing stimulus payments for individuals. With the disbursement of Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans in particular, one can find a myriad of fintech companies active in underwriting, disbursing, and servicing these government loans for small businesses. Fintech companies active in this distribution layer for government stimulus, or otherwise supporting this economic strategy, range from early-growth stage startups such as DoNotPay or Propel to large companies such as PayPal and Square. Beyond fintech, there are a number of private healthcare companies that have been attempting to develop and scale diagnostics and testing tools to augment the government’s testing capabilities, such as Everlywell or Helix. In response to a crisis of great public consequence, the balance of a society’s resources may need to be mobilized - and the dynamism of the private sector is certainly one of our greatest resources.

There are further instances in recent years of technologists from the private sector active in augmenting or otherwise supporting the delivery of government services. Perhaps one of the most notable is the effort to fix Healthcare.gov during the Obama administration, which involved a ‘tech surge’ of talent from a variety of sources, including from outside government and from programs like the Presidential Innovation Fellows. The second launch of the site also involved a small team of developers and designers called Marketplace Lite (MPL), consisting largely of technical talent from the private sector. The Obama administration also saw the creation of programs designed to improve the government’s technological capabilities, including the Presidential Innovation Fellows, the US Digital Service, and 18F. These programs, along with national nonprofits like Code for America, represent a concerted effort to improve the technical capacity of government, often with talent pipelines from the private sector.

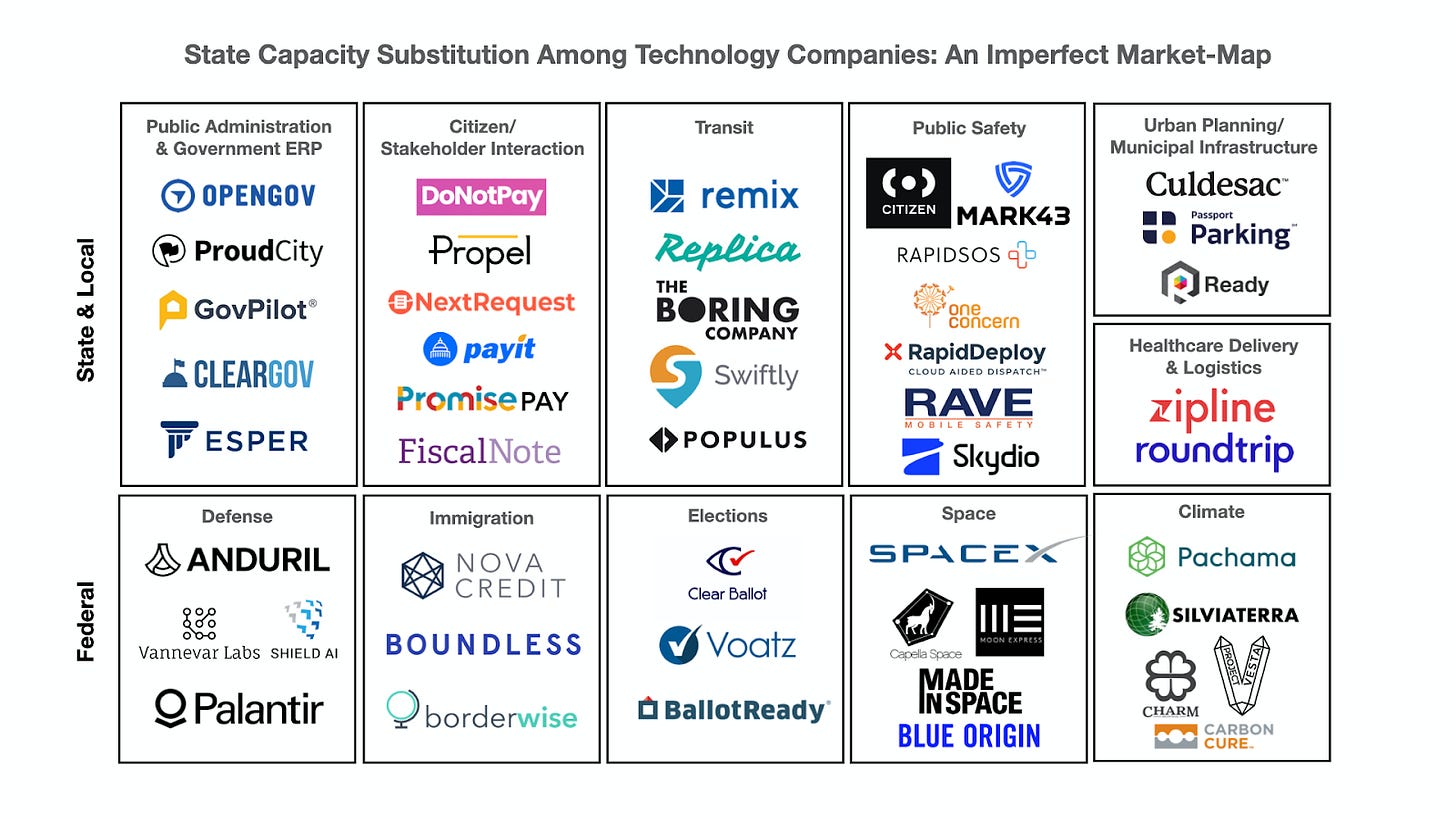

The ecosystem for technology companies and venture-backed startups that are currently supporting, augmenting, or outright performing verticalized functions of government is both incredibly expansive and diverse. A selection of companies of varying sizes that fit these descriptions, grouped by their respective relevant function of government, are shown below (under a very broad definition of product function). I believe an appropriate and precise term to describe the macro phenomenon of such companies is state capacity substitution.

Additionally, there are of course moonshot attempts from private companies and projects to perform government functions, such as cryptocurrency projects competing to create a new global reserve currency, or new conceptions of charter cities. While these projects certainly overlap with functions of government, they are also more nascent, and their exact nature, functionality, and potential effect is significantly less clear.

Driving Factors

What factors are driving this current wave of private entities, particularly technology companies and venture-backed startups, overlapping with or working in adjacent spaces to verticals of government? One possible explanation hinges on the combination of three macro trends, namely:

The post-New Deal expansion of government and establishment of a government role in a greater number of domains, well into the contemporary era.

The long-term reduction of government technical capacity at both an institutional level and in terms of technical talent flows.

Changes in citizen and public expectations in the provision of government services.

The result is a market for emerging companies that substitute for certain functions of government, particularly technology companies that are suited to performing these functions at either lower cost or for a better ‘customer’ (citizen) experience. These trends thus give rise to a phenomenon where some of these products and services are effectively functioning as substitutes to state capacity.

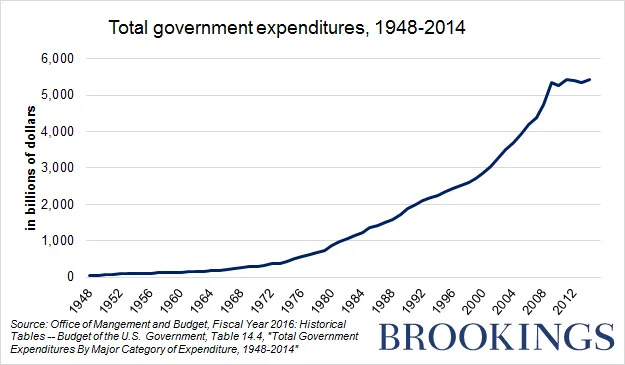

The first of these two factors is a well-documented trend over the course of the 20th century. The New Deal dramatically expanded both the role - at a policy level - of the federal government in the economy and matters of public welfare, and involved the creation of numerous ‘Alphabet agencies’, responsible for a wide variety of economic activities, social programs, and consumer welfare issues. What is perhaps more important than the actual legislation and administrative changes brought on by the Roosevelt administration in the New Deal, however, is the cultural change of an expanded perception of government in the public consciousness (i.e. a greater and more deeply ingrained expectation of the range of domains that the government should be responsible for) that arguable outlasted many of actual policies, agencies, and changes of the New Deal. For instance, it is important to remember that despite public perception, the number of federal employees relative to the population has actually decreased over the last 50 years. This expanded role of government in the public consciousness is resilient and has largely been sustained into the modern era, and may arguably be reflected in generally expanding government size and scopes when viewed over decades, with very rudimentary trends shown below.

Source

These overarching trends indicate both an actual expanding government at multiple levels, alongside a possible cultural perception of government in the public consciousness as being capable of more functions and responsible for more domains. In the context of government technology capabilities and the emergence of technology companies performing quasi-government functions, these phenomena should be considered in relation to the overarching reduction in government technical capacity.

The second trend that may contribute to the current wave of technology companies operating in government-adjacent functions is the decline of institutional technical capacity in government, along with declines in technical talent at the individual level in the public sector. The institutional decline in technical capacity is perhaps best illustrated through the defunding of the Office of Technology Assessment (OTA). An office of Congress from 1972 - 1995, the OTA was responsible for providing Congress with objective analyses of technological and scientific issues, and contributed significantly to developing innovative and cost-effective methods for the delivery of government services (e.g. electronic publishing). It was eliminated in 1995, when Congress withdrew the Office’s funding, and proposals have been made to this day to reestablish the Office. The defunding of the OTA is a stark indicator of the decline in institutional capacity of government with regards to matters of technology.

Similar trends can be observed at the level of individual talent flows in the public sector. It is a well-known priority for the government to attract strong technology teams for the purposes of policy and program delivery, as well as for public administration. Since the Great Recession, the government has been struggling to compete for technology talent with the private sector despite a brief surge in technology talent in public-sector hiring during the recession. The government technical workforce is also failing to keep pace generationally, as described by the Partnership for Public Service in a 2018 report:

“At the end of fiscal 2017, for example, data supplied by the Office of Personnel Management show that less than three percent of full-time information technology professionals were under the age of 30, while 51 percent were 50 years of age or older. Unless the government has provided significant training in modern tech, which evidence does not support, this suggests that the training and skills of the federal IT workforce are several generations out of date. If this does not change, leaders at all levels will not be able to implement programs and policies that people in America rely on.”

The results of these reductions in technical capacity can be seen in actual cases of government services delivery. The initial Healthcare.gov launch failure, as previously discussed, is one of the more well-known instances of technical barriers to the successful delivery of government programs. There are also longer term and more slowly progressing instances of the deprecation of government IT infrastructure, such as the systems used to deliver Social Security or other government benefits. Additionally, while not limited to technical infrastructure and capabilities, the current crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic has certainly highlighted weaknesses in government capacity for program design and delivery.

To be clear, there have certainly been efforts in recent years to address these technology capacity shortages, with programs such as the Presidential Innovation Fellows, the US Digital Service, 18F, or the Technology Modernization Fund. These programs highlight a certain recognition on the part of government administrators that improving government technology capabilities should be a priority. They represent an acknowledgement of and an effort to address this trend in declining technological capacity of government.

The final of these trends is related to yet distinct from the first. Experiences of the public with private consumer technology companies - particularly those with a high focus on customer experience - may have a hand in shaping citizen expectations for government services. These experiences have prompted government agencies to adopt more software-forward and technology-driven delivery systems, that emphasize “as increased transparency, new ways to approach problems, and more personalized interactions”. These expectations may make citizens/consumers more receptive and eager to use services created by private technology companies that perform these government or government-adjacent functions.

Furthermore, the first trend discussed - the expanded role of government in the public consciousness - may also function in a similar manner to create public expectations for these technology-driven services in a greater number and range of verticals. As exhibited below, the public generally prefers the status quo or even greater levels of government spending across many domains. When combined with the expectation of high-quality user experience, this expectation of expanded scale of government means the public, as ‘consumers’ of government services, are eager for high-quality products and services across a number of areas that the government is perceived to be responsible for.

Source

The combination of these trends may contribute to a situation where there is an public expectation for the government, at different levels, to perform functions across a wide-number of domains, with a high level of involvement, and deliver the programs that comprise these functions in a high-quality manner that could be comparable to private sector consumer technology companies. Conversely, the reduction over time of government technology capabilities means that the delivery of the expected breadth and quality of services may be difficult. As such, there emerges an environment that is prime for private sector technology startups to attempt to fill some of this unmet need from recipients of government services.

Distinguishing Characteristics

This trend of private companies aiming to perform quasi-government functions is anything but new. For instance, the diagram below shows the growth of the contractor workforce compared to the federal government’s overall workforce. This presence of contractors has increased significantly over the past few decades even as the numbers for other types of federal employees have remained relatively constant.

Source

In what ways is this current wave of companies - mostly technology companies or venture-backed startups - different to the overarching trend of private actors performing government functions? There are a myriad of possible responses to this question, of course. I would suggest two ways that these companies differ from traditional contractor-type actors, and how these differences may yield better results for the customers (citizens) of these companies.

Firstly, traditional government contractors are companies of massive scale, with numerous business units across one or more industries. The current wave of technology companies performing government-adjacent functions appears to be more verticalized - they are largely focused on one particular product or function, rather than seeking to expand horizontally across multiple government-adjacent functions. This verticalization may help limit concerns of private, non-governmental entities amassing large amounts of power and influence and fully co-opting government functions. Secondly, many of these companies are not actually government contractors and do not have business models built around government procurement channels. Instead, they often provide a product or service to their customers directly, such that they are focused on delivering value to their customers instead of to a separate entity responsible for their revenues; this structure may yield better results for the recipients of the services given that incentives are aligned, to a degree, between the citizens and businesses. These two characteristics of many (but certainly not all) technology companies working on government-adjacent functions may help distinguish them from other private companies in the past that have worked on delivering products and services in domains traditionally ascribed to the government.

Conclusions

It is very difficult to make an assertive prediction regarding how these trends in technology companies performing functions of government may develop in the future, given the range and variety in the products, services, business models, and macro environments that these companies operate in. Coupled with the relative nascency of many of these companies, it is also difficult to empirically assess their effects on other sectors of society. What is certain, however, is that productive collaboration and a constructive relationship between the technology industry and government is critical to the success of our communities, as the two are, perhaps now more than ever before, inseparable.